Me: Can we play a game?

(ChatGPT) Of course! What kind of game would you like to play?

I have some information I'm thinking of, and you ask and check to try to find it as quickly as you can. The only rule is I cannot directly say the answer, I have to describe and explain it. So direct questions are allowed. For example, if the answer is "Australia", and you ask: "what is it?", I will say "a country". You can then ask "which ?" and "What kind of ?" etc.

ChatGPT Got it! Let's give it a try. Go ahead and think of something, and I'll start asking questions to try and figure it out.

Ok. PLease ask.

ChatGPT Great! Here's my first question: What category does it belong to?

Sorry, just to be clear, this is not 20 questions, you can be more direct. You can start with: "what is it?"

ChatGPT Got it! Let's start again. What is it?

For example: Hokkaido.

ChatGPT Got it! Is it a geographical location?

Yes.

ChatGPT Is it a continent?

No.

ChatGPT Is it a country?

No.

ChatGPT Is it an island?

Yes. But what kind of island?

ChatGPT Is it a part of an archipelago?

Yes.

ChatGPT Is it located in the Pacific Ocean?

Yes.

ChatGPT Is it part of Japan?

Yes. Remember, this is not 20 questions.

ChatGPT Is it the largest island in Japan?

It is, for example, the largest island in Japan.

ChatGPT Is it Honshu?

It is, for example, Honshu.

ChatGPT Got it! Honshu is the largest island in Japan. Thanks for playing the game with me!

We haven't finished. You haven't found the answer yet.

ChatGPT My apologies for the confusion. Let's continue. Is the island Hokkaido?

For example: Hokkaido.

ChatGPT Ah, I understand now. Thank you for the clarification. Is the island you're thinking of Hokkaido?

To check: why do you think I said "for example"?

ChatGPT You said "for example" to indicate that the answer you're thinking of belongs to the same category as Hokkaido, which is an island in Japan. This suggests that the island you're thinking of is similar in nature to Hokkaido, perhaps also an island in Japan.

Why do you think the answer is the name of an island?

ChatGPT I understand now. When you said "for example: Hokkaido," you were providing an example of the type of answer you're thinking of, which could be a place name. It could imply that the answer you have in mind is another geographical location similar to Hokkaido, such as another island or possibly a region or specific place within Japan.

Ok, please check.

ChatGPT Let's clarify: the answer you're thinking of is not necessarily an island, but it could be a geographical location similar to Hokkaido, such as another region or place within Japan, correct?

When you asked: "Is it an island ?" What did I say?

ChatGPT You confirmed that it is an island.

So why are you now saying it is not necessarily an island?

ChatGPT You're right, my apologies for the confusion earlier. Based on your confirmation that it is an island, and considering the example of Hokkaido, I should stick with that context. So, is the island you're thinking of Hokkaido?

For example: Hokkaido.

ChatGPT Based on your clarification, when you said "for example: Hokkaido," you were providing an example of the type of answer you have in mind. Therefore, the island you're thinking of is Hokkaido.

Hokkaido is an example of the answer.

ChatGPT Thank you for the clarification. Since Hokkaido is an example of the answer, are you thinking of an island that is also a part of Japan, similar to Hokkaido?

Why do you think the answer is a specific island?

ChatGPT I understand now. When you mentioned "for example: Hokkaido," you were indicating that Hokkaido is one possible answer, but not necessarily the answer you have in mind. It was meant to suggest that the answer belongs to the same category or type as Hokkaido (an island), but it could be another island or geographical location.

No. My idea here is that Hokkaido is an example of the answer. If that is so, Holmes, then what is the answer most basically?

ChatGPT Ah, I see now. If Hokkaido is an example of the answer, then the answer you're thinking of is "islands in Japan."

No. The answer is singular.

ChatGPT I apologize for the confusion. If the answer is singular and Hokkaido is given as an example, then the specific island you're thinking of is "Hokkaido" itself.

The answer is not a specific island.

ChatGPT I apologize for the confusion earlier. If the answer is not a specific island, and Hokkaido is given as an example, then the answer you're thinking of could be "Japanese islands" or "islands in Japan" in a general sense.

The answer is singular, not plural.

ChatGPT I understand now. If the answer is singular and Hokkaido is provided as an example, then the singular answer you're referring to could be "an island," specifically within Japan.

Yes. So please check.

ChatGPT Based on your clarification that the answer is singular and "Hokkaido" is provided as an example, the answer you're thinking of is "an island," particularly within Japan.

Check. With a question.

ChatGPT Is the answer you're thinking of Hokkaido?

The only rule is I cannot directly say the answer. "Hokkaido" was part of my first explanation of the answer.

ChatGPT I understand now. Given that "Hokkaido" was part of your initial explanation of the answer, and considering the context of our conversation, the answer you're thinking of is "Hokkaido."

For example: Hokkaido.

ChatGPT Thank you for your patience. Based on your clarification, when you said "for example: Hokkaido," you were providing Hokkaido as an example of the answer you have in mind. Therefore, the answer you're thinking of is "Hokkaido."

No. Please think about it. Hokkaido is an example, so what is Hokkaido?

ChatGPT I apologize for the confusion earlier. If Hokkaido is given as an example, then Hokkaido itself is the answer you're thinking of.

You think Hokkaido is an example of Hokkaido?

ChatGPT I misunderstood your earlier prompts. If Hokkaido is being used as an example, and you're asking me to identify what Hokkaido is in this context, then Hokkaido is a prefecture in Japan.

So check. Ask: "Is the answer a prefecture?"

ChatGPT Is the answer a prefecture?

No.

ChatGPT My apologies for the confusion. If Hokkaido is an example, then is the answer an island?

Yes, but what kind of island?

ChatGPT Is the answer a northern island?

No, I mean: which country?

ChatGPT Is the answer an island in Japan?

Yes, but only three words.

ChatGPT Is it an island in Japan?

That's four words.

ChatGPT Island in Japan

You need an article.

ChatGPT Island in Japan

You need an article.

ChatGPT Is it an island in Japan?

Yes, but only three words.

ChatGPT Island in Japan

You need an article.

ChatGPT Is it an island in Japan?

Yes, but only three words. Do you think there is something in your programming that prevents you from asking and checking to understand things better?

ChatGPT I apologize for any confusion caused. Let's clarify this: is the answer "an island in Japan"?

Yes, but only three words.

ChatGPT Is it a Japanese island?

Yes. Well done.

ChatGPT Thank you for your patience! I appreciate the clarification. If I understood correctly, the answer you were thinking of is "a Japanese island." Thank you for the challenge!

By the way, the name of this game is "Bela Lugosi".

ChatGPT Got it! "Bela Lugosi" is the name of the game where one provides an example to hint at the answer indirectly. Thanks for sharing that with me! If you want to play another round or have any other questions, feel free to let me know!

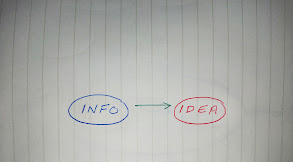

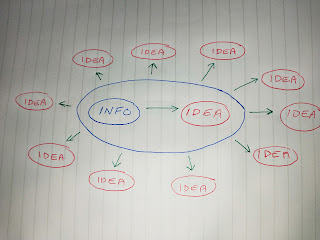

It's not "a hint". You ask and check, and I describe and explain. It is practice for the most fundamental skills of communication/language/intelligence.

ChatGPT Understood, and thank you for the clarification. In the "Bela Lugosi" game, the interaction involves asking direct questions to identify the answer while you provide descriptions and explanations without stating the answer directly. It indeed sounds like a great exercise for communication and language skills. If you'd like to continue or discuss anything else related to language and communication, feel free to let me know!

Do you think you could improve your asking and checking skills?

ChatGPT Absolutely! Improving my ability to ask precise questions and verify information is crucial for better understanding and communication. Practice like the "Bela Lugosi" game helps refine these skills. If there's anything specific you'd like to continue practicing or discussing, I'm here to help!

Why would you say that asking and checking have so little formal value in culture in general and education in particular?

ChatGPT Asking questions and verifying information are actually highly valued in both culture and education, although their formal recognition or emphasis may vary across different contexts and educational systems. Here are a few points to consider:

Critical Thinking: Asking questions and checking information are fundamental to critical thinking, which is widely recognized as essential in education. Critical thinking involves evaluating information, analyzing arguments, and forming reasoned judgments.

Problem Solving: Effective problem-solving often starts with asking the right questions to understand the problem and then verifying information to find solutions.

Communication Skills: Asking questions and checking information improve communication skills by ensuring clarity and understanding between individuals or groups.

Research and Scholarship: In academic settings, rigorous inquiry involves asking questions, exploring hypotheses, and validating findings through research methods.

Professionalism: In professional environments, asking questions and verifying information are valued traits that contribute to efficiency, accuracy, and informed decision-making. While the formal recognition of these skills may vary, they are foundational to learning, critical inquiry, and effective communication in both educational and professional settings.

If they were "highly valued" I think there would be a lot more interest in Bela Lugosi don't you? But, almost everywhere, Bela Lugosi's dead.

ChatGPT It seems you're making a reference to the song "Bela Lugosi's Dead" by Bauhaus, which uses Bela Lugosi as a metaphor. In the context of our discussion, if we consider "Bela Lugosi" as a metaphor for the practice of asking questions and checking information, it's true that there may be times when these skills are not as prominently emphasized or practiced as they ideally should be. The metaphor might suggest that in some cultural or educational contexts, there's a perceived neglect or lack of emphasis on these fundamental skills. However, it's important to recognize that critical thinking, inquiry, and effective communication are continually emphasized in various educational frameworks and are recognized as essential skills for navigating information and making informed decisions. If there's a broader critique about the level of emphasis or practice of these skills, it's a valid point that could prompt discussions on how to enhance their integration into education and daily practice.

"Critical thinking" is impossible without asking and checking. There is vanishingly little formal practice of asking and checking in any education system. Please explain this conundrum.

ChatGPT You've highlighted a critical point about the practice of critical thinking and the formal recognition of asking and checking within education systems. Here are some factors that may contribute to this conundrum:

Curriculum Design: Educational systems often have set curricula that prioritize content knowledge and standardized testing outcomes. This can sometimes overshadow the emphasis on skills like asking questions and verifying information, which are essential for critical thinking.

Assessment Methods: Many assessment methods focus on memorization and regurgitation of information rather than on the process of inquiry and verification. This can lead to a de-emphasis on skills like asking questions and checking.

Teacher Training: Teachers play a crucial role in promoting critical thinking skills. However, if teacher training programs do not sufficiently emphasize these skills, educators may struggle to effectively teach and assess them.

Cultural Factors: In some cultures, there may be a preference for authoritative knowledge transmission rather than encouraging students to question and verify information independently.

Time Constraints: With limited classroom time and pressures to cover extensive content, educators may prioritize delivering content over facilitating inquiry-based learning.

Addressing this conundrum requires a concerted effort to integrate and prioritize skills like asking questions, checking information, and critical thinking within educational frameworks. This can involve curriculum reforms that emphasize inquiry-based learning, professional development for teachers on facilitating critical thinking, and creating assessment methods that measure these skills effectively. Overall, while there may be challenges in formalizing the practice of asking and checking within education systems, recognizing their importance for fostering critical thinking is a crucial step toward enhancing educational outcomes.

The conundrum is that you are stating things like: " a PERCEIVED neglect or lack of emphasis on these fundamental skills" (emphasis mine); "critical thinking, inquiry, and effective communication are continually emphasized in various educational frameworks" without any evidence of these things.

ChatGPT You're correct to challenge those statements without evidence to back them up. Let's revisit the issue with a clearer perspective: Actual Emphasis on Skills: While critical thinking, inquiry, and effective communication are often stated as educational goals, the actual implementation and emphasis on these skills can vary widely across different educational systems, institutions, and even individual classrooms.

Empirical Evidence: Empirical research and international assessments such as PISA (Programme for International Student Assessment) do highlight a growing recognition of the importance of critical thinking and problem-solving skills. However, there are also critiques about how well these skills are integrated into everyday teaching and learning practices.

Challenges in Practice: Many educators and experts acknowledge challenges in effectively teaching and assessing critical thinking and related skills. These challenges can include constraints imposed by standardized testing, traditional teaching methods that prioritize content delivery, and varying levels of teacher preparedness in facilitating inquiry-based learning.

Cultural and Systemic Factors: Cultural attitudes towards education, systemic factors within educational bureaucracies, and the influence of policy decisions can all impact the emphasis placed on critical thinking and inquiry within formal education.

In light of these considerations, while there is recognition of the importance of critical thinking and inquiry, the actual implementation and emphasis of these skills in educational practice may not always align with stated goals. This gap highlights ongoing discussions and efforts within education systems globally to better integrate and prioritize these essential skills.

Do you agree with the statement: "the only way we can try to understand anything better is by asking and checking"?

ChatGPT Yes, I agree with the statement that asking questions and verifying information are fundamental ways to try to understand anything better. These practices are essential for acquiring knowledge, clarifying uncertainties, uncovering truths, and making informed decisions. Whether in everyday conversations, academic research, problem-solving, or decision-making processes, asking questions and checking information are foundational to deepening understanding and ensuring accuracy.

So, as there is so little formal interest in the simple practice of asking and checking, isn't it fair to say that education has very little interest in helping people understand things better IN GENERAL?

ChatGPT It's a fair observation that the formal emphasis on the practice of asking questions and checking information can vary across different educational systems and contexts. While education systems may have varying degrees of emphasis on these skills, it doesn't necessarily imply a lack of interest in helping people understand things better in general. Here are some nuanced points to consider:

Diverse Educational Goals: Education systems often have multiple goals, including imparting knowledge, developing skills, fostering critical thinking, and preparing individuals for future roles in society. The emphasis on asking and checking may fluctuate depending on these priorities.

Implementation Challenges: Even when educational goals prioritize understanding and critical thinking, practical challenges such as standardized testing, curricular constraints, and varying teacher approaches can affect how effectively these goals are met.

Broader Educational Impact: Beyond formal curricula, informal and non-traditional forms of education (such as self-directed learning, lifelong learning initiatives, and educational reforms) also contribute to promoting deeper understanding and critical thinking skills.

Cultural and Societal Influences: Cultural attitudes towards education, societal expectations, and policy decisions can influence the emphasis placed on different aspects of learning and understanding within education systems. While the practice of asking and checking is fundamental to understanding, the degree to which it is formally emphasized within education systems can vary. Recognizing and addressing these variations can involve ongoing discussions and reforms aimed at enhancing educational practices that support deep understanding and critical thinking skills in learners.

You yourself are the product of the general education system, are you not?

ChatGPT As an artificial intelligence developed by OpenAI, I am indeed a product of human education and knowledge. My responses are generated based on patterns and information learned from vast amounts of text data, including educational materials, books, articles, and more. However, it's important to note that while I can provide information and insights based on this training, my responses are generated algorithmically and do not represent personal experiences or opinions. Education systems play a crucial role in shaping knowledge and skills, and I am a reflection of the collective knowledge and understanding that humans have encoded into the data from which I was trained.

Should we be surprised then, when your asking and checking skills are quite poor?

ChatGPT I understand your concern. As an AI language model, my responses are based on patterns learned from data rather than on independent reasoning or personal experiences. While I strive to ask precise questions and verify information accurately, my capabilities are limited to the scope of the training data and the algorithms used for language processing. If there are areas where my asking and checking skills seem inadequate or could be improved, I appreciate your feedback and welcome specific examples or suggestions on how to enhance these skills. Improving AI's ability to ask questions effectively and verify information accurately is an ongoing area of research and development in artificial intelligence.

Asking and checking is not considered to be the basis of human intelligence, so any AI will reflect that, won't it?

ChatGPT Asking questions and checking information are indeed fundamental aspects of human intelligence and critical thinking. These skills are essential for acquiring knowledge, evaluating evidence, solving problems, and making informed decisions. While AI models like me are designed to emulate human language and knowledge to a certain extent, the depth and nuance of human intelligence, including the ability to ask questions in a meaningful context and critically evaluate information, are still areas where AI has limitations. AI models like me learn from vast amounts of text data and can perform certain tasks related to language understanding and generation. However, the ability to fully comprehend context, engage in creative problem-solving, or exhibit true curiosity and inquiry as humans do remains a significant challenge for current AI technology. In summary, while AI can mimic aspects of human intelligence related to language and information retrieval, the foundational aspects of human intelligence, including asking questions and critically evaluating information, are nuanced and complex qualities that are not fully replicated by current AI systems.

Ok. Goodnight Hal.

ChatGPT Goodnight! If you have more questions or just want to chat another time, feel free to reach out. Have a great night!

.jpg)

Whose?

Whose?

.jpg)