Ever since I saw this for the first time, maybe 35 years ago, I was always slightly baffled by the phrase: "We choose to go to the Moon and do the other things, not because they are easy, but because they are hard."

What does "and do the other things" mean, I wondered? Why did Kennedy just presume his audience would know what these other things were? Or was it some sophisticated rhetorical device that I was unaware of? Should I start using it to give whatever I was saying some much-needed gravitas?

However, just last week I happened upon a fuller version of the speech:

With context, it is obvious what "and do the other things" is referring to, and here is the point: we can get a better understanding of anything by understanding its context. However, it is not usual for people to even acknowledge this.

It is worth reiterating then, that: we can only understand information by its connected ideas, and that any information is embedded within a web of connections of information and idea(s) that constitutes the actual matrix that we live within.

That matrix includes sushi recipes, computer networks, and The Matrix.

It can include anything, as the context of anything is everything. In communication, the fundamental organic process ensures that communication is always both incredibly simple and dazzilingly complex at the same time.

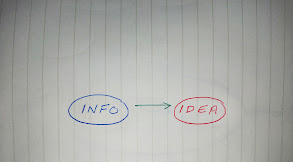

The fundamental process is always:

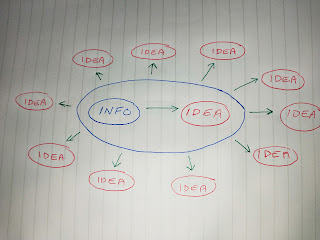

however, like a stone cast into a pond, any first step of the fundamental communicative process ripples out in all directions:

and anything else you can think of... as well as everything you can't.

Happily, the process of evolution has allowed us a brain that, while constantly computing millions of points of context without any conscious oversight, allowing us to do achieve such dazzilingly complex tasks as walking to the shops, also has the capacity to sort information out by cutting out those connections deemed unnecessary. In short, we can ignore possible connections in order to arrive at the most useful.

The immediate context.

To take an example, remember this guy?

Joseph Kony, abductor of children, leader of child soldiers, wanted in Uganda for various atrocities including rape of young girls, and abducting them for use as sex slaves.

In 2012, a short documentary film about him and his crimes entitled Kony 2012 became the first video on YouTube to gain 1 million likes. It is estimated that nearly half of American youth were aware of the video within a week after its release. The video called for action against Kony, and celebrities including Justin Beiber, Bill Gates, and Kim Kardashian, lined up to endorse the cause.

Although it received support, others with a more in-depth knowledge of the situation rightly called it out as slacktivism, with one specialist ponting out that the simple solution of just raising awareness is "a beautiful equation that can only work so long as we believe that nothing in the world happens unless we know about it ... only works in the myopic reality of the film, a reality that deliberately eschews depth and complexity."

Joseph Kony, evil man ------------> put a sticker up in your school.

Kony + sticker -----------------------> I feel good.

What happened to Joseph Kony?

Nothing.

As of 2023, it is thought he remains in hiding in Darfur.

The Kony 2012 example also serves to illustrate how the new media, the Facebooks YouTubes, and tik-toks, providing simple pleasure as they are designed to do, (Former Facebook executive says Facebook designed to be as addictive as cigarettes), are contributing to a general cuture where less thought and effort is given to try to understand anything better, as locked in as we are to immediate gratification and the increasing economic satiation of our most basic animal needs.

Of course, human beings have always been like this. Our most basic operating system is the same as the other animals, where any information is immediately plugged into ideas of emotion and sensation. However, we do have the capacity for asking and checking (to get better describing and explaining) way beyond our fellow creatures, but the fact remains that it is generally discouraged, and specifically inhibited in education as demonstrated by the complete lack of any formal importance attached to the practice, testing, or grading of asking and checking.

Our ability to wield questions to help us cut through the forest of information we live in has allowed us to get this far. Better communication, of which asking and checking is the foundation, is behind all improvement in human history.

Why stop now, just when things are getting interesting?

Down the memory hole: other things

They got them back, right?.

Could another Prime Minister express such self confidence in mocking the idea of Long Covid with a complete ignorance of another debilitating disease?

Mind you, it was always thus, and as more context becomes available we can get a clearer idea of the people we allow to rule us:

Well, ok. But it's not like he was in Dallas the day of the Assassination, right?

.jpg)

Whose?

Whose?

.jpg)